History of board games - From the dawn of time until today

A travel through mankind's civilizations with the help of board games

Tony

2/15/202549 min read

Introduction

Ladies and gentlemen, today we embark on an extraordinary journey through the annals of history, exploring one of humanity’s oldest and most enduring pastimes—board games. From the dawn of civilization to our modern digital age, board games have served as more than just entertainment; they have been tools for education, strategic thinking, social bonding, and cultural expression. Their evolution reflects our collective human story, from ancient Egypt and Mesopotamia to the high-tech world of today. Let us traverse time and continents to uncover the fascinating history of board games and their profound influence on civilization.

Ancient Beginnings: The First Board Games

The origins of board games date back to prehistory, with some of the earliest known examples found in burial sites and ancient ruins. These games were more than mere amusement; they carried religious, strategic, and cultural significance. Let’s have a look at some of these games.

Senet

Among the earliest known board games is Senet, an ancient Egyptian game that dates back to at least 3100 BCE. This game, whose name means "passing" or "the game of passing," was more than just a pastime; it held deep spiritual and cultural importance in Egyptian society. Over time, Senet faded into obscurity but was rediscovered in the modern era, sparking new interest in its history, rules, and impact on gaming culture.

The game was played on a rectangular board consisting of 30 squares arranged in three rows of ten. Small figurines and game pieces, often made of ivory or wood, were used to navigate the board. Though no written record of the exact rules survives, scholars have pieced together possible gameplay mechanics based on ancient texts and depictions.

One of the earliest depictions of Senet appears in tomb paintings from the Old Kingdom period (c. 2686–2181 BCE), showing people engaged in play. It is believed that Senet originally started as a secular game before gradually taking on religious connotations.

By the time of the New Kingdom period (c. 1550–1070 BCE), Senet had become more than just a recreational activity. It was linked to the Egyptian belief in the afterlife. The game was thought to represent the journey of the soul through the Duat, the Egyptian underworld, with pieces symbolizing a player's progress toward spiritual rebirth and eternal life. Some tomb inscriptions even suggest that playing and winning at Senet was a metaphor for achieving favor with the gods and successfully navigating the afterlife.

Pharaohs and high-ranking individuals often had ornate Senet boards buried with them, indicating its significance. One of the most famous Senet boards was found in the tomb of Tutankhamun, crafted with luxurious materials and intricate carvings. The association between Senet and religious beliefs also led to the inclusion of spells and prayers in the game’s later iterations, further solidifying its spiritual importance.

The Decline and Disappearance of Senet

Despite its long-standing popularity, Senet eventually fell out of favor. By the time of the Ptolemaic period (c. 305–30 BCE), Greek and Roman influences in Egypt introduced new forms of entertainment, leading to the decline of many indigenous games, including Senet. Over the centuries, the exact rules of the game were forgotten, and it was lost to history.

I would like to emphasize something about board games that I have learned from studying Senet. Good games travel. There is something unique about Senet. Even though it was played by Egyptians for many centuries until the Ptolemaic period, evidence of it existing outside of Egypt during that period is scarce. It seems that its deep religious theme was what kept other cultures from embracing Senet, let alone the fact that its whole connection to the Afterlife might seem macabre and frightening.

The Rediscovery of Senet

The modern rediscovery of Senet began in the 19th and early 20th centuries with archaeological excavations in Egypt. Egyptologists uncovered numerous Senet boards in tombs and temple ruins, sparking academic interest in its history and gameplay. Scholars like Howard Carter, famous for discovering King Tutankhamun’s tomb, and Sir William Matthew Flinders Petrie played significant roles in uncovering and analyzing Senet artifacts.

In the 1940s, Egyptologist Irving Finkel attempted to reconstruct the rules of Senet using ancient inscriptions and other Egyptian texts. Since no definitive rulebook was ever found, historians developed various interpretations of how the game might have been played. These reconstructions led to renewed interest in the game, inspiring board game enthusiasts and historians alike to study and recreate it.

Senet in the Modern World

Today, Senet has seen a revival among historians, archaeologists, and board game enthusiasts. The rise of historical board games and digital gaming has also led to the creation of virtual Senet adaptations, allowing people worldwide to engage with this ancient pastime.

Senet’s legacy extends beyond just being a rediscovered game; it has influenced modern board games that involve strategy and chance. Games like backgammon, which also rely on movement dictated by dice-like tools, bear striking similarities to Senet. Some historians even speculate that Senet could be one of the ancestors of modern race-based board games.

Conclusion

Senet stands as a testament to humanity’s long-standing love for games and strategic thinking. More than just a game, it was a bridge between leisure and spirituality in ancient Egyptian society. Its rediscovery and reconstruction have allowed modern audiences to appreciate and experience a game that entertained pharaohs and commoners alike. While the exact rules may remain a mystery, the cultural and historical impact of Senet endures, reminding us of the rich legacy of board games throughout history.

The Royal Game of Ur

The Royal Game of Ur is one of the oldest known board games, with origins dating back over 4,500 years to ancient Mesopotamia. This game, rediscovered in the 20th century, has provided scholars with valuable insights into early gaming culture, ancient social interactions, and the evolution of board games. The game’s discovery in royal tombs, along with cuneiform inscriptions detailing its rules, has cemented its place as a crucial artifact in the study of ancient civilizations. From the dawn of humanity to the present day, the Royal Game of Ur remains a testament to the timeless appeal of board games.

Discovery and Historical Background

The Royal Game of Ur was first unearthed in the 1920s by British archaeologist Sir Leonard Woolley during excavations at the Royal Cemetery of Ur, located in present-day Iraq. Ur was one of the most prominent Sumerian city-states, flourishing around 2600 BCE. Among the numerous artifacts found in the tombs were beautifully inlaid game boards, decorated with shell, lapis lazuli, and red limestone. These boards, along with associated gaming pieces, indicated that the game was enjoyed by royalty and nobility.

Further discoveries revealed that versions of this game were played across a vast geographical area, including Persia, the Levant, and even Egypt. Variations of the board have been found in archaeological sites from Iran to the Mediterranean, suggesting that it was a widely recognized and culturally significant game in the ancient world.

Understanding the Rules Through Cuneiform Tablets

While the Royal Game of Ur was known from its physical remains, it was the discovery of cuneiform inscriptions that allowed researchers to reconstruct its rules. In the late 19th century, several clay tablets containing references to the game were found, but it wasn’t until the 20th century that British Museum curator Irving Finkel deciphered a Babylonian tablet from around 177 BCE, which provided detailed instructions on how the game was played.

The rules describe a race game where two players move their pieces along a specific path based on dice throws. The game utilized tetrahedral dice marked with dots, and the movement of pieces was dictated by the number of dots facing upwards. The goal was to move all one’s pieces across the board before the opponent. The tablet also described special markings on the board that had implications for strategy, such as granting extra turns or offering protection from captures. This discovery was crucial, as it gave modern scholars an understanding of how the game was enjoyed in antiquity.

Influence on Ancient Civilizations

The Royal Game of Ur was more than just a pastime; it played a significant role in social and religious life. The game boards were often found in the graves of high-ranking individuals, suggesting that the game held spiritual or ceremonial significance. Some scholars propose that the game was associated with divination, as the movement of pieces was dictated by dice, which may have symbolized the will of the gods.

The game’s widespread presence across ancient cultures also points to early trade networks and cultural exchanges. As it spread to different regions, variations developed, influencing later board games such as the modern backgammon.

Decline and Rediscovery

Like many ancient customs, the Royal Game of Ur gradually faded from mainstream popularity, likely due to shifting cultural dynamics and the emergence of new games. However, echoes of its design and mechanics can be seen in various historical board games that followed.

Interest in the game was revived after Woolley’s discoveries, and its rules, reconstructed by Finkel, allowed historians, archaeologists, and board game enthusiasts to engage with it once more. Museums began displaying replicas, and modern versions of the game have been created for educational and entertainment purposes.

The Game in Modern Times

Today, the Royal Game of Ur has enjoyed a resurgence among historians, archaeologists, and board game aficionados. Enthusiasts have recreated the game, and adaptations are available for those who want to experience the strategic and competitive nature of this ancient pastime. The British Museum, among other institutions, regularly showcases the game and even hosts interactive sessions where visitors can play according to the ancient rules.

Furthermore, the game serves as an educational tool, allowing researchers to explore early human cognition, probability theory, and the role of games in social structures. Its enduring legacy highlights how board games have always been an integral part of human culture, transcending time and geography.

Conclusion

The Royal Game of Ur is a fascinating example of humanity’s long-standing love for board games. From its origins in Mesopotamian royal tombs to its modern revival, the game has demonstrated remarkable resilience. It offers a glimpse into the past, showing how people in ancient times sought entertainment, engaged in strategic thinking, and possibly used games for religious or divinatory purposes. Thanks to archaeological discoveries and the deciphering of ancient texts, this ancient game continues to captivate and inspire players today, preserving a piece of history that bridges the ancient and modern worlds.

Mancala

Mancala is one of the oldest known board games, with origins tracing back thousands of years. Found in various forms across Africa, the Middle East, and parts of Asia, it has evolved into a family of games played under different names and rules. From the ancient kingdoms of Africa to modern-day competitions, Mancala remains a game of strategy, skill, and cultural significance.

Origins of Mancala: The Dawn of Strategic Board Games

The precise origins of Mancala are difficult to determine, but archaeological evidence suggests the game dates back over 3,000 years. Early Mancala boards or similar playing surfaces have been found in ancient African settlements, including Sudan and Egypt. The game was likely played using holes dug into the ground and small stones, seeds, or shells as playing pieces.

Historians believe Mancala may have emerged as a way for ancient agricultural societies to simulate planting and harvesting, a concept mirrored in its gameplay. The name "Mancala" itself derives from the Arabic word naqala, meaning "to move," highlighting the essence of the game—strategic movement of pieces across a board.

The spread of Mancala across Africa and the Middle East is tied to the migration of people, trade routes, and cultural exchanges. In ancient Egypt, evidence of Mancala-like games was found in temple carvings and tombs, indicating its role in entertainment and possibly religious rituals. Similarly, in the Kingdom of Aksum (modern Ethiopia and Eritrea), playing boards carved into stones suggest that Mancala was an integral part of the local culture.

In Asia, variations of Mancala emerged as trade networks expanded. Merchants and travelers likely introduced the game to the Indian subcontinent and the Malay Archipelago, where it was embraced and modified into region-specific versions.

The Evolution and Spread of Mancala Variants

Mancala has evolved into numerous regional variants, each with its own unique set of rules. This game has traveled to so many places in the world, like few others. Here are some of the most notable versions and regions:

Africa

Burkina Faso

Togo

Ghana,

Ivory Coast,

Nigeria,

Cameroon,

Gabon,

Senegal,

Cape Verde,

Gabon,

Equatorial Guinea,

Congo,

Tanzania,

Kenya,

Malawi,

Comores,

Madagascar,

Uganda

South America

Guayana,

Suriname,

Brazil,

Caribbean

Antigua & Barbuda,

Barbados,

Dominica,

Grenada,

Guadeloupe,

Santa Lucia,

American Virgin Islands,

Jamaica,

Cuba

Central Asia

Kazakhstan,

Kyrgyzstan,

Tajikistan,

Uzbekistan,

Turkmenistan,

Russia,

Mongolia,

China,

Afghanistan,

Turkey

South Asia and parts of Oceania

Philippines,

Mariana Islands,

Malaysia,

Singapore,

Indonesia,

Thailand,

Maldives,

Sri Lanka,

India

Names

Oware

Awari,

Awele,

Awale,

Aualè,

Owari,

Owani,

Kale,

Kboo,

Poo,

Langa Holo,

Ti,

Warri,

Wari,

Weri,

Wori,

Woro,

Wahree,

Wol,

Ouril,

Ouri,

Ourin,

Ayo,

Ayoayo,

A-i-ú,

Adi,

Adji,

Adji kui

Songo

Songo ewondo,

Songa

Bao

Bao La Kiswahili,

Bawo,

Morahha

Omweso

Mweso

Toguz Kumalak

Toguz Korgool

Sungka

Sungca,

Sunka,

Chonka,

Chonku,

Chuncajon,

Jungka,

Chuka,

Tchonka,

Main Congkak,

Congkak,

Congklak Dakon,

Galatjang,

Mak khom,

Naranj,

Ohvalhu

Pallanguli

Alaguli Mane,

Vamana guntalu,

Satkoli

Kalah

Mancala in the Modern World

Today, Mancala continues to be played in homes, schools, and tournaments worldwide. New versions of the game have introduced it to new audiences, while traditional wooden boards remain popular among enthusiasts. International tournaments, particularly for variants like Oware and Toguz Kumalak, have further solidified Mancala as a competitive game.

Beyond entertainment, Mancala serves as a tool for cognitive development. It enhances strategic thinking, planning, and mathematical skills, making it a valuable educational resource. Some cultures even use Mancala as a means of teaching historical traditions and social values.

Conclusion

The journey of Mancala from ancient civilizations to the digital age is a testament to its enduring appeal. As one of humanity’s oldest games, it continues to bridge cultures and generations, preserving a legacy of strategy and intellectual challenge. Whether played on a high-tech app or a carved wooden board in an African village, Mancala remains a game of timeless significance, uniting people through the simple yet profound act of moving small stones across a board.

Mehen

One of the earliest known board games, Mehen, emerged from the heart of ancient Egypt and carried profound religious symbolism. This mysterious game, often associated with the serpent deity Mehen, the coiled one, has intrigued historians and archaeologists alike. Its influence extended beyond Egypt, shaping games and cultural practices for centuries.

Dating back to around 3000 BCE, Mehen was one of the oldest known board games in history. Evidence of the game has been found in archaeological sites from the Predynastic and Early Dynastic periods of Egypt (c. 3100–2700 BCE), including tombs such as those in Abydos and Saqqara. These discoveries suggest that Mehen was a popular pastime among the elite and may have held religious significance.

The game itself was played on a round board resembling a coiled snake, divided into segments. This spiral-shaped design is what gave the game its name, as Mehen was also the name of an Egyptian protective serpent deity. Scholars believe that the game was played with small figurines, often lion-shaped pieces and marbles or counters that moved along the serpent’s back.

Mehen: The Coiled Serpent God

The game was closely tied to the Egyptian deity Mehen, a protective serpent god often depicted as coiling around the sun god Ra to safeguard him from threats during his nightly journey through the underworld. This association suggests that Mehen was more than just a game; it may have had a ritualistic or symbolic function in funerary practices. Some scholars theorize that playing Mehen could have been a reenactment of divine protection, possibly even used to secure safe passage in the afterlife.

Serpents held complex roles in Egyptian mythology. While often associated with chaos and destruction, as seen in the case of Apep, they could also represent protection and renewal. The duality of the serpent is reflected in Mehen's role as a guardian and guide, reinforcing the idea that the game had a deeper meaning beyond mere entertainment.

The Decline of Mehen

By the Middle Kingdom (c. 2000 BCE), Mehen began to decline in popularity. This period saw the rise of games like Senet, which were more straightforward in their rules and possibly easier to manufacture. By the time of the New Kingdom (c. 1550 BCE), Mehen had largely vanished from Egyptian culture, with little evidence suggesting its continued play.

The decline of Mehen may have been linked to shifting religious beliefs. As Egyptian mythology evolved, the role of Mehen as a protective deity diminished, and his symbolic representation in board gaming may have followed suit. Additionally, the increasing influence of Mesopotamian board games could have contributed to the overshadowing of Mehen by more contemporary alternatives.

Influence and Legacy

Despite its decline, Mehen left a lasting impact on board game design and cultural practices. Similar spiral-based games have appeared in other ancient civilizations, including in the Levant and Mediterranean regions. Some scholars suggest that elements of Mehen may have inspired later games, though direct connections remain speculative.

The symbolism of a coiled serpent also persisted in mythology and religious iconography. The protective and cyclical nature of the serpent reappeared in various forms across different cultures, from Norse mythology’s Jörmungandr to the Mesoamerican deity Quetzalcoatl.

Mehen in the Modern World

In recent years, there has been a resurgence of interest in ancient games, leading to attempts to reconstruct Mehen based on archaeological findings. Enthusiasts and historians have recreated the game using traditional materials, experimenting with potential rulesets. These efforts have brought Mehen back into the public eye, allowing modern players to experience a pastime that was once enjoyed by the ancient Egyptians.

Moreover, Mehen has found its way into pop culture and historical board game research. With the rise of digital media and historical gaming communities, the game has seen adaptations in various forms, from tabletop recreations to video game references.

Conclusion

Mehen stands as a fascinating relic of ancient Egyptian culture, offering insight into the early development of board games and their intertwining with religious beliefs. While much about the game remains a mystery, its significance as both a form of entertainment and a spiritual symbol is undeniable. From the dawn of civilization to modern revivals, Mehen continues to capture the imagination of historians, gamers, and enthusiasts alike, reminding us of the enduring power of games to connect past and present.

Five Lines

Among the many board games that have emerged throughout history, one of the most ancient and influential is Five Lines (Greek: Pente Grammai). This game, often considered a precursor to modern strategy games, dates back to ancient Greece and beyond, having been played by great warriors, poets, and thinkers. It was so deeply woven into Greek culture that it found its way into mythology and literature, including The Iliad of Homer.

Origins: From the Dawn of Mankind to Early Civilizations

The exact origins of Five Lines are difficult to pinpoint, but scholars believe that it evolved from early board games played in Mesopotamia and Egypt. Archaeological findings suggest that board games were a crucial part of early human societies, serving as entertainment and a means of developing strategic thinking.

By the time of classical Greece, Five Lines had become a well-known pastime. The game was played on a board with five parallel lines, and players used small tokens or stones to move across them according to the roll of dice or another form of randomization.

Rules and Gameplay

The exact rules of Five Lines remain uncertain, but historical descriptions suggest that it was a strategy-based race game. Players moved their pieces along the five lines in a structured manner, attempting to reach a designated end-point first. The use of dice indicates that chance played a role, but skillful positioning and movement were also essential to victory.

Mentions in Classical Literature: Homer - Achilles and Ajax

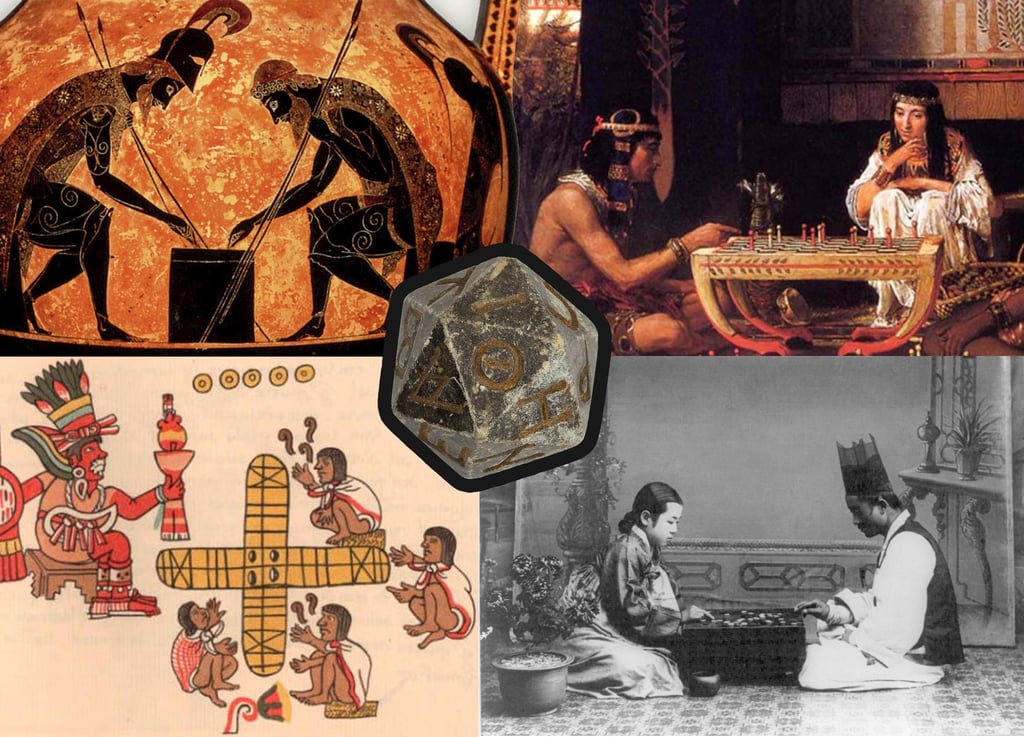

One of the most famous references to Five Lines comes from Homer’s The Iliad, where the game is depicted in a significant scene involving two legendary Greek warriors: Achilles and Ajax. The passage, found in later artistic interpretations rather than directly in Homer’s text, illustrates the two great heroes engaging in a board game during a lull in the Trojan War.

This depiction was later immortalized in Greek pottery, such as the famous black-figure amphora attributed to Exekias, dating to the 6th century BCE. In this image, Achilles and Ajax sit across from each other, deeply engrossed in the game. Their posture and expressions indicate intense concentration, symbolizing not only the strategic nature of the game but also its importance in Greek society.

The game’s inclusion in mythological contexts suggests that it was more than just a form of entertainment—it represented intelligence, competition, and even fate. The portrayal of Achilles and Ajax playing Five Lines reinforces the idea that even the mightiest warriors valued mental prowess alongside physical strength.

Spread and Influence on Other Civilizations

As Greek culture expanded through colonization and conquest, so too did Five Lines. The game spread across the Mediterranean, influencing the Romans, who adopted and adapted various Greek pastimes.

Roman Variations and Influence

The Romans, known for their love of board games such as Latrunculi, likely played a version of Five Lines. The game’s emphasis on strategy and luck would have fit well with the Roman appreciation for skillful gaming.

As the Roman Empire expanded, board games traveled to distant provinces, embedding themselves in different cultures. Variants of Five Lines may have influenced later medieval European games, eventually leading to the development of more sophisticated board games during the Renaissance.

Decline and Rediscovery in the Modern Era

With the fall of the Roman Empire and the onset of the Middle Ages, many ancient games faded from common use. However, some of their elements survived in later strategic board games.

By the 19th and 20th centuries, historians and archaeologists began rediscovering ancient board games through excavations and literary analysis. The significance of Five Lines was recognized in Greek vases and texts, leading to renewed scholarly interest in its mechanics and role in society.

Today, board game enthusiasts and historians attempt to reconstruct Five Lines, using historical artifacts and writings to recreate its gameplay. Modern board games such as Backgammon and Pente are thought to share conceptual similarities with Five Lines, continuing its legacy in the gaming world.

Conclusion: A Legacy That Endures

Five Lines is more than just an ancient board game; it is a symbol of strategic thought, cultural expression, and the shared human desire for challenge and competition. From its roots in early civilizations to its influence on Greek warriors like Achilles and Ajax, and its spread across the ancient world, Five Lines played a crucial role in shaping gaming history. Whether played in the courts of kings or by warriors before battle, Five Lines remains a testament to humanity’s enduring love for strategy and competition.

Latrunculi

Latrunculi stands out as a fascinating relic of ancient times, originating in the Roman Empire and enjoyed by soldiers and civilians alike. The name Latrunculi derives from the Latin word latrones, meaning "soldiers" or "mercenaries," reflecting the game’s warlike nature.

Origins and Early Influences

While Latrunculi is primarily associated with the Roman Empire, its roots likely extend further back to earlier civilizations such as the Greeks and Egyptians. Many scholars believe Latrunculi was influenced by the Greek game Petteia, described by classical authors such as Plato and Aristotle as a tactical battle game played on a grid-like board.

As Rome expanded its dominion, it absorbed cultural elements from conquered territories, including board games. The Romans refined and popularized Petteia, transforming it into Latrunculi, which became a beloved pastime among soldiers, intellectuals, and aristocrats. Archaeological evidence of Latrunculi boards and playing pieces has been found across the Roman Empire, from Britain to North Africa, demonstrating its widespread appeal.

Latrunculi in the Roman Empire

During the height of the Roman Empire (27 BCE – 476 CE), Latrunculi was a common game played in military camps, taverns, and homes. It was especially favored by Roman legionaries, who used it to sharpen their strategic thinking and tactical planning. The game’s mechanics reflected real battlefield maneuvers, mirroring how soldiers outflanked and captured enemies.

The standard Latrunculi board varied in size but was typically an 8x8 or 12x8 grid. The pieces, often made of glass, bone, or stone, represented opposing armies. Unlike modern chess, there was no king or special piece; instead, players aimed to surround and capture enemy pieces through strategic positioning. The game’s rules were never explicitly documented, but historians have reconstructed them based on references in ancient texts and archaeological findings.

One notable mention of Latrunculi comes from the Roman poet Ovid, who alludes to it in his works, suggesting its popularity among the Roman elite. Additionally, the game is referenced in Strategemata, a treatise on military tactics, further reinforcing its association with warfare.

The Decline and Rediscovery of Latrunculi

With the fall of the Western Roman Empire in the 5th century CE, many Roman customs, including Latrunculi, began to fade. The game saw a decline in popularity as newer strategy games emerged across Europe, influenced by cultural exchanges with the Middle East and Asia. Chess, which arrived in Europe via the Islamic world, gradually replaced Latrunculi as the dominant strategy game.

Despite its decline, Latrunculi was never entirely forgotten. Medieval texts occasionally referenced it, and variations of the game persisted in certain regions. It was rediscovered in the 19th and 20th centuries by historians and archaeologists who examined Roman-era artifacts, including boards carved into stone surfaces at ancient forts.

The Modern Revival of Latrunculi

Today, Latrunculi enjoys renewed interest among historians, board game enthusiasts, and reenactment societies. Modern reconstructions of the game’s rules, based on historical research, have allowed players to experience it much as the Romans did. Digital versions and board game adaptations have also introduced Latrunculi to a new generation, preserving its legacy as one of the oldest known strategy games.

Several museums and historical groups organize Latrunculi tournaments, emphasizing its educational value in teaching strategic thinking, history, and Roman military tactics. The game’s simplicity, combined with its depth, continues to captivate players, proving that the strategic mind of a Roman soldier is still relevant today.

Conclusion

From its possible origins in ancient Greece and Egypt to its heyday in the Roman Empire and its modern revival, Latrunculi has traversed centuries as a testament to humanity’s love for strategic play. Though it may not be as widely known as chess or Go, its influence on board game history is undeniable. Whether played on a reconstructed Roman board or a digital platform, Latrunculi remains a fascinating glimpse into the past and a reminder of the timeless nature of strategy and intellect.

Go

The board game Go is one of the oldest and most profound strategic games ever created. With a history stretching back thousands of years, Go has played a significant role in the intellectual and cultural development of several civilizations. From its mythological origins to its current status as a globally recognized mind sport, the journey of Go is a fascinating one.

Origins of Go: A Game Born from Strategy

The origins of Go trace back to ancient China, with some accounts dating its invention as early as 2300 BCE. According to legend, the game was created by Emperor Yao, a semi-mythical ruler, as a tool to teach his son, Danzhu, discipline, foresight, and strategic thinking. Whether or not this tale is historically accurate, it highlights Go’s deep roots in the development of intellectual and philosophical traditions in China.

Some historians believe Go was initially used for divination and military strategy, mirroring the structure of war formations. The game’s grid-like board and emphasis on controlling territory might have been inspired by early military tactics, reinforcing the idea that Go was not merely a pastime but a method of training the mind for governance and warfare.

Go in Ancient China: A Scholar’s Game

By the time of the Zhou Dynasty (1046–256 BCE), Go had evolved into a game played primarily by scholars, military leaders, and aristocrats. It became an essential component of the four classical arts, alongside calligraphy, painting, and playing the guqin (a traditional musical instrument). The game was deeply embedded in Confucian and Daoist philosophies, with its emphasis on balance, patience, and adaptation mirroring the principles of these schools of thought.

Confucius himself, while not a documented player, referenced Go in his teachings, emphasizing the importance of cultivating patience and intelligence in young learners. During the Han Dynasty (206 BCE–220 CE), Go became widespread among scholars and was often depicted in art and poetry as a symbol of intellectual refinement.

The Spread of Go: Korea and Japan

Go traveled beyond China’s borders, reaching Korea and Japan between the 5th and 7th centuries CE. In Korea, the game, known as "baduk," was embraced by the aristocracy and Buddhist monks, who viewed it as a meditative practice. Korean dynasties, such as the Goryeo (918–1392) and Joseon (1392–1897), fostered the game’s development, and professional players eventually emerged.

In Japan, Go found an especially fertile ground for growth. The game arrived through Buddhist monks and Chinese scholars, but it was during the Tokugawa shogunate (1603–1868) that Go reached new heights. The government officially supported Go institutions, and the shogun himself sponsored a ranking system for players. The famous "Four Go Houses"—Hon’inbō, Inoue, Hayashi, and Yasui—were established, each producing generations of skilled players and contributing to the standardization of rules and techniques. Go became a key element of samurai education, as strategic acumen in the game was considered reflective of battlefield intelligence.

Go in the Modern Era: Global Recognition

By the late 19th and early 20th centuries, Go began to attract interest outside East Asia. Western intellectuals and mathematicians, fascinated by its complexity, introduced the game to Europe and the Americas. World War II briefly disrupted Go’s growth, particularly in Japan, but the postwar era saw a resurgence of interest, especially with the rise of international tournaments and the founding of the International Go Federation in 1982.

One of the most significant events in modern Go history occurred in 2016 when AlphaGo, an artificial intelligence program developed by DeepMind, defeated professional player Lee Sedol. This victory marked a turning point in AI research and demonstrated the computational depth of Go, previously considered too complex for machines to master. The match also renewed global interest in the game, inspiring new generations of players and researchers.

Conclusion: A Game for the Ages

Go has survived and thrived for thousands of years, from ancient Chinese courts to the digital age. Its influence on military strategy, philosophy, and artificial intelligence underscores its status as more than just a game—it is a reflection of human thought and ingenuity. As Go continues to evolve, its legacy as one of the world’s most intellectually stimulating games remains intact, ensuring its place in history for generations to come.

Hnefatafl

Hnefatafl stands out as one of the most fascinating and historically significant games, particularly in Northern Europe. Originating from the early medieval period, Hnefatafl—also known as the "King's Table"—was a game of strategy and asymmetric warfare that reflected the Viking Age's war tactics and societal structure. Over time, it spread across different cultures, underwent numerous variations, and ultimately faded before experiencing a modern revival.

Origins: The Dawn of Hnefatafl

Hnefatafl belongs to a family of ancient Tafl games, which were prevalent in Northern Europe before the introduction of chess. Though the exact origins are uncertain, evidence suggests that the game was played as early as the 4th century CE. The name "Hnefatafl" translates from Old Norse to "King’s Table," hinting at the importance of the central king piece in gameplay.

Archaeological finds provide valuable insights into the game's early presence. Boards and playing pieces have been discovered in Viking burial sites across Scandinavia, the British Isles, and even as far as Ireland and Russia. These findings suggest that the game spread through Viking trade routes and conquests, reflecting the era’s interconnected world. The game likely evolved from older Roman and Germanic Latrunculi-style games, which also emphasized strategy and military maneuvering.

Gameplay and Strategy: A Test of Wits

Hnefatafl is unique among board games due to its asymmetric nature. Unlike chess, where both players have identical pieces, Hnefatafl sets one player in the role of a king and his defenders, while the other controls an overwhelming force of attackers. The objective varies depending on the version played, but typically:

The king and his defenders aim to escape to a board edge or corner.

The attackers seek to capture the king by surrounding him on all four sides.

Pieces move in a straight line like a rook in chess but cannot jump over others.

Capture occurs by sandwiching an opponent’s piece between two of one’s own, much like go or latrunculi.

This balance of power creates a game of high tactical depth, requiring foresight, careful planning, and an understanding of positioning. The asymmetric setup also reflects Viking battle strategies, where a small elite force might defend against a much larger enemy.

Expansion Across Europe: Cultural Adaptations

As Viking influence spread, so too did Hnefatafl. The game was recorded in medieval literature and chronicles, including mentions in Icelandic sagas like the Orkneyinga saga and Frithiof’s Saga. It was not only a pastime but also a representation of martial skill and intellect, played by noblemen and warriors alike.

Variations of Tafl games developed across different regions, each with its own unique modifications:

Brandubh (Ireland): A smaller, 7x7 version of the game.

Alea Evangelii (Britain, c. 12th century): A more complex 19x19 board with additional rules.

Tawlbyund (Wales): A version mentioned in historical Welsh texts.

Tablut (Lapland/Sápmi): Documented in the 18th century by Swedish botanist Carl Linnaeus, this is one of the most well-preserved variants, influencing modern reconstructions of Hnefatafl.

These adaptations show how the game was not merely confined to Viking society but integrated into various medieval cultures, each adding their own twists to the rules.

The Decline and Rediscovery

The prominence of Hnefatafl declined with the rise of chess in the 11th-13th centuries. Chess, brought from the Islamic world through Spain, gradually overshadowed Tafl games due to its structured elegance and royal endorsement across Europe.

By the 16th and 17th centuries, Hnefatafl had almost disappeared. However, its memory survived in scattered historical references and a few remaining boards and pieces found in archaeological digs. The most significant rediscovery came in the 18th century, when Carl Linnaeus observed the game being played among the Sámi people in Lapland and recorded its rules under the name Tablut. This documentation would later prove crucial in reconstructing the game.

Modern Revival: From Obscurity to Popularity

The late 20th and early 21st centuries saw a resurgence of interest in Hnefatafl, driven by historical enthusiasts, researchers, and board game revivalists. Several factors contributed to this revival:

Archaeological discoveries: New findings of Tafl boards reignited curiosity about the game.

Academic research: Studies of medieval texts and Linnaeus' accounts helped reconstruct possible rule sets.

Viking culture revival: A growing fascination with Viking history, popularized by films, TV shows like Vikings, and reenactment societies, brought Hnefatafl back into focus.

Board game renaissance: A broader trend in tabletop gaming led to new interest in historical and asymmetric strategy games.

Today, multiple reconstructions of Hnefatafl exist, and the game is enjoyed worldwide. Modern versions vary slightly, incorporating elements from Tablut, Brandubh, and Alea Evangelii, but the essence remains: a game of cunning, strategy, and asymmetric warfare.

Conclusion: A Legacy of Strategy and Warfare

Hnefatafl is more than just a board game; it is a window into the Viking Age, a reflection of medieval tactics, and a testament to the cultural exchange facilitated by trade and conquest. While it may have been eclipsed by chess for centuries, its modern revival ensures that this unique and historic game continues to challenge and entertain players worldwide.

Chess

Chess, often regarded as the "game of kings," has captivated minds for over a millennium. With its origins rooted in ancient strategy games, chess has evolved across cultures and centuries, shaping and being shaped by the civilizations that embraced it. From its earliest form as Chaturanga in ancient India to the modern grandmaster showdowns and AI competitions, chess has stood the test of time as one of the most intellectual and beloved board games in history.

The Origins: Chaturanga and Ancient India

The earliest known precursor to chess is Chaturanga, a game that emerged in Gupta Empire India around the 6th century CE. Chaturanga, meaning "four divisions of the military" (infantry, cavalry, elephants, and chariots), reflected the structure of ancient Indian armies. The game was played on an 8x8 board, much like modern chess, and involved strategic movements that would later influence the game’s evolution.

Chaturanga spread through trade routes and cultural exchanges, influencing neighboring civilizations. As it traveled westward, it underwent modifications that would transform it into the chess we recognize today.

Shatranj: The Persian Adaptation

As Chaturanga moved into Persia around the 7th century, it evolved into Shatranj. The Persians modified some of the game’s pieces and rules, introducing features such as the concept of "check" (Shah) and "checkmate" (Shah Mat), both derived from Persian phrases. The game became immensely popular in the Persian courts, and it was here that chess gained its association with intellectual prowess and noble competition.

After the Islamic conquest of Persia, Shatranj spread throughout the Islamic Caliphate, reaching the Middle East, North Africa, and Spain. It was during this period that chess gained a stronghold in Europe.

Chess in Medieval Europe

By the 9th and 10th centuries, chess had firmly taken root in Europe, brought by the Moors to Spain and by returning Crusaders from the Middle East. Medieval European society embraced chess as a game of strategy, often linked to warfare and military tactics.

During the 15th century, chess underwent its most significant transformation in Spain and Italy. The rules were revised to make the game faster and more dynamic. The most notable changes included:

The queen (previously a weaker piece) was given the ability to move any number of squares in any direction, significantly increasing its power.

The bishop, once limited to moving only two squares diagonally, was granted unrestricted diagonal movement.

The concept of castling, en passant, and pawn promotion were refined.

These changes led to what is now known as "modern chess."

The 20th Century: The Golden Age of Chess

The 20th century was a golden age for chess, characterized by intense rivalries, national pride, and technological advancements. The establishment of FIDE (Fédération Internationale des Échecs) in 1924 provided a governing body for international chess competitions.

Chess was also transformed by technology. The 1997 match between Garry Kasparov and IBM’s Deep Blue marked the first time an AI defeated a reigning world champion, ushering in an era where computers could challenge and even surpass human players.

Chess in the Digital Age

With the rise of the internet, chess experienced a renaissance. Online platforms such as Chess.com, Lichess, and Playchess made chess accessible to millions worldwide. Players could now compete against opponents from different countries instantly.

The COVID-19 pandemic accelerated this trend, with online chess tournaments gaining unprecedented popularity. Magnus Carlsen, the reigning world champion, helped popularize online chess with the Magnus Carlsen Invitational, an online tournament featuring top grandmasters.

The Future of Chess

Chess continues to evolve with advancements in AI, data analysis, and new formats like Chess960 (Fischer Random Chess). With AlphaZero demonstrating a revolutionary self-learning approach, artificial intelligence is now an essential tool for top players' training and analysis.

As chess remains deeply intertwined with technology, education, and popular culture, its legacy as the world’s most strategic game is secure for generations to come.

Conclusion

From its ancient roots in Chaturanga to modern digital tournaments, chess has remained a symbol of intelligence, strategy, and mental endurance. It has transcended cultural and geographical boundaries, uniting minds across centuries. Whether played on a wooden board in a medieval court or on a smartphone app today, chess continues to captivate and challenge players, proving that it is, indeed, the ultimate timeless game.

Snakes and Ladders

Few games have stood the test of time like Snakes and Ladders. With roots tracing back thousands of years, this seemingly simple game has been a tool for education, philosophy, and morality, reflecting the values of the societies that played it. From its early origins in ancient India to its transformation into a global pastime, Snakes and Ladders has influenced countless generations, teaching them about fortune, virtue, and vice.

The earliest version of Snakes and Ladders can be traced back to ancient India, where it was known as "Moksha Patam." Historians believe the game originated around the 2nd century BCE, though some sources suggest it may be even older. It was not merely a pastime but a tool for imparting spiritual and ethical lessons.

Moksha Patam was deeply rooted in Hindu philosophy and was designed to teach players about karma, destiny, and the consequences of their actions. The ladders represented virtues such as faith, generosity, and humility, which helped individuals ascend toward enlightenment (moksha). Conversely, the snakes symbolized vices like anger, greed, and lust, which led to spiritual downfall and suffering.

The game's numerical structure was often based on religious or philosophical themes. The board typically had 72, 84, or 100 squares, each representing steps toward enlightenment. Different versions incorporated teachings from Hinduism and Buddhism, reinforcing the idea that good deeds elevated individuals toward a higher plane of existence, while bad deeds led to setbacks.

Spread to Other Civilizations

During the medieval period, Snakes and Ladders spread beyond India, reaching Persia and later the Islamic world. The game adapted to different cultural and religious contexts while maintaining its core moral and educational function. In Islamic societies, the game was often framed within moral teachings from the Quran, emphasizing divine justice and moral behavior.

By the late 19th century, British colonial rule facilitated the introduction of the game to England. British soldiers and officials, fascinated by the simplicity and deeper meaning of Moksha Patam, brought it back to Europe. In the process, the game underwent changes to appeal to a Western audience. The moral lessons were softened, with ladders and snakes representing more secular concepts of good and bad fortune rather than spiritual salvation.

The Victorian Era and Western Adaptation

In England, the game was first published commercially in 1892 under the name "Snakes and Ladders." The British version retained some of the moral aspects, with virtues like kindness and hard work helping players advance, while laziness and dishonesty caused setbacks. However, the religious undertones were largely removed, making it more suitable for a secular audience.

The game quickly gained popularity and was marketed as a children's game, emphasizing lessons in morality and personal conduct. By the early 20th century, Snakes and Ladders became a staple in British households, reflecting Victorian values of discipline and character-building.

Introduction to the United States and the Rise of Commercial Board Games

In the 1940s, the game reached the United States, where it was produced by the Milton Bradley Company under the name "Chutes and Ladders." The name change was primarily to make the game more appealing to children, as ladders remained a positive metaphor, but snakes were seen as too intimidating. In this version, moral lessons were further simplified—good deeds like helping others or eating healthy led to upward movement, while negative behaviors such as lying or neglecting chores resulted in sliding down.

During the mid-20th century, Snakes and Ladders (or Chutes and Ladders) became a classic American board game, cementing its place alongside other household favorites like Monopoly and Candy Land. The game was particularly valued for its ease of play, allowing children of all ages to enjoy it without requiring reading skills or complex strategy.

Modern Popularity and Variants

Snakes and Ladders has remained a popular game worldwide. Today, it exists in countless versions, adapted to different cultures and themes. From religious and educational variations to pop-culture-themed editions, the game continues to be a vehicle for storytelling and moral education.

In India, traditional versions of Moksha Patam are still played, particularly during religious festivals. In modern board game culture, variations include educational adaptations that teach math, language, and even environmental awareness.

The digital age has also transformed Snakes and Ladders. Online versions and mobile apps have made the game accessible to a global audience, often incorporating animated graphics and interactive elements. Despite these changes, the fundamental essence of the game remains intact—teaching players that life is a mixture of ups and downs, fortune and misfortune, virtue and vice.

Philosophical and Psychological Insights

Beyond its role as a pastime, Snakes and Ladders has been used as a metaphor for life itself. The game is entirely based on chance, with no player skill involved, reinforcing the idea that fate plays a significant role in human existence. Some psychologists argue that playing Snakes and Ladders helps children develop patience, resilience, and an understanding of the consequences of their actions.

Moreover, the game’s reliance on dice rolling reflects themes found in various philosophical and religious teachings: the unpredictability of life, the role of luck, and the importance of making ethical choices even when faced with uncertainty.

Conclusion: A Game That Transcends Time

From its origins as a sacred Indian game of moral enlightenment to its transformation into a global pastime, Snakes and Ladders has maintained its core theme—life is full of highs and lows, and our choices determine our path. While modern versions may downplay its original philosophical significance, the game remains a cherished and enduring part of human culture.

Whether played on a traditional board, a digital screen, or a classroom setting, Snakes and Ladders continues to entertain, educate, and inspire. It serves as a reminder that the journey of life is unpredictable, but with patience and virtue, we can always strive to reach the top.

Patolli

Patolli is an ancient board game with a fascinating history that spans thousands of years, influencing both the culture and social dynamics of various civilizations, particularly in Mesoamerica. Though it is most famously associated with the Aztecs, it is believed that the game dates back much earlier, reaching back to the Pre-Columbian period. The game wasn't just a recreational pastime; it played a significant role in ritual, religion, and even gambling, sometimes with life-altering stakes.

Patolli is believed to have originated in Mesoamerica, likely during the Olmec period (around 1500 BCE to 400 BCE), with evidence of its existence seen in artwork and archeological finds. The game was initially played by the Olmecs, but its greatest fame came with the Aztecs, who adopted and popularized it. The game's appeal spread far beyond the commoners, becoming part of the elite's social gatherings and royal courts.

The term “Patolli” is derived from the Nahuatl language, the language of the Aztecs, where it means "to gamble" or "to wager." This highlights a key element of the game: it wasn’t merely a pastime, but a game where players could stake significant personal assets, even their own freedom. Its widespread popularity during the height of the Aztec Empire (14th to 16th century CE) illustrates its importance in both social and religious practices.

The Game's Cultural Significance

Patolli was far more than just a game; it had a deep connection with Mesoamerican spirituality and cosmology. The Aztecs, for example, viewed the game as an expression of the gods' will. They believed that playing Patolli was a form of communication with their deities, particularly with gods such as Tezcatlipoca and Huitzilopochtli. The randomness of the dice roll was seen as a way to leave decisions up to fate, guided by divine intervention.

The board itself was symbolic, often designed in the form of a cross or an X, representing the four cardinal directions—an important concept in Mesoamerican cosmology. The design of the game was also a reflection of the Aztec's view of the universe, and the movement on the board represented the journey of the soul through life, death, and the afterlife.

Players used brightly colored stones or beans as tokens, which they moved around the board in accordance with the roll of the dice. The dice, usually made from materials such as bones, stones, or clay, were sacred objects in their own right, often intricately decorated with symbols or glyphs related to specific gods or rituals.

Patolli as a Form of Gambling

Gambling was a major aspect of Patolli, and it wasn’t just a casual form of entertainment. The stakes could be incredibly high, and the game’s outcome had real-life consequences. It was common for players to wager valuable possessions, including gold, precious stones, and even slaves. In fact, losing a game of Patolli could result in a player forfeiting their freedom, as captives or slaves could be won or lost depending on the outcome of the game. For those at the top of the social ladder, a game of Patolli could mean the loss of wealth or status.

The stakes of these games could also extend to political and religious ramifications. It’s not uncommon for high-ranking priests or warriors to gamble for positions of power or influence, with the outcome of the game affecting their social and political standing. This made Patolli more than just a game; it became a symbolic act of fate and power. It was used as a tool for resolving disputes or as a method of reinforcing social hierarchies.

In the world of Mesoamerican societies, where ritual and sacrifice were deeply intertwined with everyday life, it was not unusual for games of Patolli to be played in conjunction with ceremonies or as part of larger religious observances. Some games were held in honor of gods, with the results interpreted as signs from the deities themselves.

The game could also be a form of a public spectacle. Patolli tournaments were sometimes held in large public spaces, with spectators cheering for their favored players. These games could be grueling and extended for hours, with the tension and stakes increasing as the wagers grew. To heighten the intensity, certain rituals might be performed, such as invoking gods or making offerings before the game started.

The Spanish Conquest and the Decline of Patolli

With the arrival of the Spanish conquistadors in the early 16th century, the fate of Patolli and other Mesoamerican cultural practices changed dramatically. The Spanish, under figures like Hernán Cortés, sought to impose their own religious and cultural practices upon the indigenous people. This included the eradication of native religious ceremonies and games, which they considered pagan.

Despite the efforts of the Spanish to suppress the game, Patolli did not vanish entirely. It was clandestinely played among indigenous communities and adapted into the broader culture. Many of the practices surrounding gambling, fate, and ritual that were integral to Patolli found their way into various forms of modern-day games and betting, but much of the original cultural significance was lost.

The Spanish also introduced European versions of board games, such as chess and backgammon, which gradually became more popular among the ruling class. As colonial society evolved, these games replaced many of the traditional Mesoamerican games, including Patolli.

Patolli's Legacy in the Modern World

Though Patolli itself largely disappeared from mainstream culture following the Spanish conquest, its legacy still endures. Modern board games, including some forms of dice games and race-based games, show the influence of Patolli’s structure. The game’s key elements—chance, strategy, and stakes—have been incorporated into many modern gaming systems, often in ways that reflect the same gambling-driven excitement that was a cornerstone of Patolli.

Additionally, the idea of betting one's freedom or wealth in a game, while not common today, is still found in some forms of gambling and competitive play. Patolli’s emphasis on the interplay of fate, choice, and risk is something that resonates in modern gaming and gambling cultures, as players continue to test their luck and risk personal stakes.

Conclusion

The history of Patolli is a rich tale of culture, religion, and risk. From its origins in the ancient civilizations of Mesoamerica to its role in the imperial courts of the Aztecs, Patolli was far more than a game—it was a manifestation of divine will, a form of socialization, and a high-stakes gamble that could change the course of a player's life. Even though the game largely disappeared after the Spanish conquest, its influence on the world of board games and gambling remains clear. Today, Patolli serves as a testament to the enduring human fascination with fate, chance, and the pursuit of fortune.

Puluc (aka Bul)

Puluc, also known as Bul, is an ancient board game that has roots stretching back thousands of years. Its cultural, historical, and social significance paints a vivid picture of early human societies and their interplay with leisure, strategy, and warfare. The game reflects martial values, deeply ingrained in the societies that played it, and showcases the intricate link between games, rituals, and conflict. Spanning from pre-Columbian Mesoamerica to modern times, Puluc offers valuable insight into the evolution of games as tools for entertainment, teaching, and reflecting societal values.

Origins of Puluc: The Dawn of Civilization

Puluc, whose alternate name, Bul, is frequently used in some regions, traces its origins to the ancient civilizations of Mesoamerica, particularly the Maya civilization of Central America. As early as the Preclassic period (1000 BCE to 250 CE), archaeological evidence suggests that a game similar to Puluc was in play. Early Mesoamerican peoples, had a complex understanding of games, with many involving elements of strategy, mathematics, and even metaphysical beliefs. Puluc, in particular, serves as an example of how games were not just about entertainment but were deeply intertwined with the rituals, social hierarchies, and martial cultures of the time.

In ancient Mesoamerica, games were often seen as mirrors of life itself: they symbolized the ongoing struggle between opposing forces, the balance of power, and the relationship between life and death. Puluc was a reflection of these themes, incorporating military and strategic aspects that echoed the warriors’ roles in society. The game mirrored the martial societies in which it was played, where physical and intellectual prowess were highly valued, especially for those in elite or warrior classes.

Puluc’s Structure: A Game of War and Sacrifice

At its core, Puluc is a game of capture, where two players engage in a battle to eliminate or capture the opponent's pieces, often reflecting a real-world struggle between two forces. The game typically involves a board divided into a grid, which is marked in a specific way that corresponds to rules around capturing or “sacrificing” pieces. This system of capturing was not just a reflection of military strategy but was also infused with symbolic significance.

In the martial societies of the ancient Maya, captives were often taken in warfare and used in ritual sacrifices. Puluc’s game mechanics mirrored this concept, where pieces could be “captured” and removed from the board, symbolizing the capture of enemy soldiers in battle. Some accounts of the game’s structure even suggest that after capturing an opponent’s pieces, the player could sacrifice them in the sense of removing them from the game in a symbolic reenactment of a ritual sacrifice. This ritualistic element tied the game to the sacred and the supernatural, emphasizing the significance of warfare in the social and religious life of the Maya.

This connection between warfare and sacrifice within the game itself highlights the importance of Puluc in reinforcing social values and religious ideologies. It served as a tool for teaching martial skills, strategic thinking, and the social order of ancient Mesoamerican society, where military prowess and the ability to capture enemies were of paramount importance.

Puluc and the Maya Civilization: Symbolism of Power

Puluc was especially popular in the Maya civilization, which spanned a vast region covering parts of modern-day Mexico, Guatemala, Belize, Honduras, and El Salvador. Among the Maya, games were more than just recreational; they were woven into the fabric of their culture and their perception of the world. The Maya often associated games with the forces of creation and destruction, the struggle between life and death, and the cosmic battle between the gods and their enemies. Puluc embodied these concepts, serving as a tool for both entertainment and religious expression.

The Maya saw games as a means of negotiating the balance of power. The act of capturing pieces in Puluc was not just about outwitting an opponent; it symbolized victory over an enemy and, by extension, the divine favor in a cosmic struggle. This is especially evident in Maya iconography, where the imagery of warfare, sacrifice, and games is often intertwined. The Maya ballgame, known as Pok-A-Tok, was another game that held deep symbolic meaning, and while it was different from Puluc, it similarly reflected themes of warfare and sacrifice. Puluc, while more abstract than Pok-A-Tok, was nonetheless another example of how games were used to enact and reinforce the martial and religious values of ancient Mesoamerican civilizations.

In terms of physical design, the game was played with stones or other small pieces, which were arranged on a grid-like board. These pieces represented warriors or captives, with the overall goal being to eliminate the opponent's pieces through strategic movement. The use of the word sacrifice in relation to the game may have carried specific meanings beyond just gameplay mechanics, serving as a way to remind players of the broader implications of victory and defeat in the context of war and religion.

Puluc in Post-Classic and Colonial Mesoamerica

By the time of the Postclassic period (900 CE to 1500 CE) in Mesoamerica, Puluc had solidified its role in the culture of several Mesoamerican civilizations. The Aztecs, though most famous for their ballgame, are also believed to have played similar games of strategy that involved capturing and eliminating pieces. The influence of Puluc likely spread throughout Mesoamerican societies due to the cultural exchange that occurred via trade, conquest, and religious ceremonies.

As European explorers and colonizers arrived in the Americas, many indigenous practices, including traditional games like Puluc, were either suppressed or transformed. However, some aspects of these games persisted through oral traditions and regional variations, eventually being passed down to later generations.

The Influence of Puluc on Modern Games

Though Puluc itself is no longer widely played today, its influence can still be seen in the structure of modern strategy games. Its blend of tactics, movement, and capturing echoes the foundational concepts in games like chess, go, and even modern board games like Risk or Settlers of Catan. These games often emphasize strategy, territorial control, and the ability to eliminate or capture pieces — elements that were central to Puluc’s appeal.

Puluc also represents one of the earliest examples of games that combined strategic thought with martial symbolism. The dynamics of war, power, and ritual were embedded within the game’s structure, helping to shape the way societies perceived and engaged with conflict. The martial culture reflected in the game mechanics provides valuable insight into the role of warfare in shaping not only the political landscape but also the cultural and recreational activities of ancient peoples.

Conclusion: Puluc’s Legacy in History

Puluc, or Bul, is more than just an ancient game; it is a cultural artifact that provides a window into the social, military, and spiritual life of Mesoamerican civilizations. From its origins in the Preclassic Maya period to its spread across ancient Mesoamerica, Puluc served as a vehicle for teaching martial strategy, symbolizing the struggle between life and death, and reinforcing the power structures that governed these societies.

The game’s connection to warfare, ritual sacrifice, and the martial culture of the time speaks to the importance of conflict in shaping early civilizations. As a reflection of the values, beliefs, and practices of these ancient peoples, Puluc offers a deeper understanding of how games were used as more than just pastimes—they were tools for socializing, educating, and even legitimizing power. Though the game is no longer widely played, its legacy continues to influence modern strategic games and remains a testament to the enduring importance of games as cultural expressions across time.

The Bear Hunt Family of Board Games

The bear hunt family of board games has a long and fascinating history that dates back to the dawn of mankind, and these games have evolved into numerous variations across different cultures and regions. Originating as primitive activities meant to simulate the thrill and strategy of hunting, these games have since influenced ancient civilizations and modern gameplay. From the early versions of these games played on rough terrains to the intricate and strategic rules of contemporary adaptations, the bear hunt family has left a lasting legacy in the world of board games.

The concept of hunting games can be traced back to the hunter-gatherer societies of prehistory. Early humans often used simulations to practice their hunting skills or to pass time in groups. The bear, as a symbol of strength and ferocity, became a natural focal point for these games. Ancient civilizations began to form their own versions of these hunting games, often with symbolic connections to their cultures, beliefs, and practices.

The early bear hunt games were simple and rudimentary, usually played on dirt or stone surfaces. Players would use stones, sticks, or carved objects to represent the bear and its hunters. These games were a way to recreate hunting expeditions that mirrored the real-life importance of hunting for food and survival. The strategies involved in these games reflected the tactical and cooperative skills required for a successful hunt.

As these games spread across different civilizations, they underwent various modifications to suit the local culture and resources. By the time written history began to form, we can observe that hunting games had already spread across continents.

Mesopotamia and the Ancient Near East

In the ancient Mesopotamian region, board games played a central role in social and religious gatherings. The Sumerians, Akkadians, and Babylonians, who inhabited this region around 3000 BCE, were known to have played early versions of board games with a similar structure to modern-day bear hunt games. These games were not only recreational but also ritualistic. They often simulated battle, hunting, or other survival scenarios. The symbolism of the bear hunt game was likely connected to the idea of overcoming obstacles and mastering nature—a theme present in many Mesopotamian myths.

Ancient Egypt and China

In Egypt, the game of Senet, while it was not directly related to bear hunts, its strategic nature laid the foundation for games that would evolve into the bear hunt family. Similarly, in ancient China, games like Weiqi (known in the West as Go) evolved into more complex forms of strategy. These games influenced later hunting-themed board games, like those of the bear hunt family, which borrowed from their tactical gameplay and abstract representations of challenges.

India and the Influence of Bagha Chall

In India, the bear hunt family of games took root through one of its notable early versions: Bagha Chall. Bagha Chall, also known as "The Game of Tigers and Goats," traces its origins back to the ancient kingdom of Bengal. In this game, one player controls tigers, while the other controls goats. The objective is for the tigers to capture the goats, while the goats work together to block the tigers' movements. Though this game does not specifically feature a bear, it shares the same hunting and animal-centric theme, showing how the tradition of hunting games became embedded in the culture of ancient civilizations.

Variations Across Cultures

Over the centuries, the bear hunt family of board games expanded into many variations, each with its own unique twists. The regional differences reflect the diverse ways in which the game evolved to fit the norms, landscapes, and cultural contexts of each society. Here are some of the prominent variations in the bear hunt family of games:

Adugo

One of the lesser-known but fascinating variants of the bear hunt game family is Adugo, which originated in West Africa. Adugo is a two-player strategy game where one player controls an animal (often represented as a bear) and the other controls smaller creatures that represent hunters. The object is for the hunters to encircle the bear. This game, like many in the bear hunt family, emphasizes tactical thinking and prediction.

Fox Games

The Fox Games, including Fox and Geese, are another well-known variant. This game involves players using foxes and smaller animals (geese) on a grid. The fox's objective is to catch the geese, while the geese try to escape. The dynamics of the game mirror the hunt as well as the strategy behind it.

Rimau-Rimau

Rimau-Rimau, a Southeast Asian version of the bear hunt game, originated in Malaysia and Indonesia. In this game, one player controls the tiger, and the other controls a series of goats. This game shares similarities with Bagha Chall, as it also involves a predator-prey relationship. Rimau-Rimau has an added complexity, where the tiger must navigate a more difficult path to capture the goats, thus requiring advanced strategic planning.

Sz'kwa

Sz'kwa is a variation from the indigenous cultures of North America, particularly among the Native American tribes. This game, also known as "The Bear Hunt Game," uses a simplified board where players simulate the roles of hunters, animals, and the land they must traverse. Sz'kwa was often played during ceremonial events, and it featured symbolic gestures of the interconnectedness between humans, animals, and nature.

Main Tapal Empat

Main Tapal Empat, originating from the Philippines, is another variant of the bear hunt family, where players use markers to simulate an animal chase. This game often holds deeper cultural significance, as it reflects the traditional practices of hunting and living in harmony with nature.

Len Choa and Sher-Bakar

Len Choa and Sher-Bakar are variations from Central Asia, where the games take on the cultural form of pastoralism and nomadic hunting. These games often feature larger boards and more intricate gameplay, simulating the vast open spaces where ancient hunters once roamed.

Bagh Bandi and Komikan

The Indian subcontinent produced several other variants such as Bagh Bandi and Komikan. In Bagh Bandi, one player controls the tiger, while the other controls the goats, in a variation similar to Bagha Chall. Komikan, on the other hand, uses different symbols and rules for the hunter-prey relationship, often reflecting ancient myths and stories.

Catch the Hare and Buga-Shadara

In Catch the Hare, a popular variation found in various parts of Africa, one player takes the role of the hunter, while the other represents the hare. The hunter attempts to catch the hare, mimicking a chase across a grid-like board. Buga-Shadara, a game from Central Asia, similarly involves a chase mechanism and tactical planning.

Lambs and Tigers, Kaooa

The more contemporary versions of the bear hunt family, such as Lambs and Tigers and Kaooa, still maintain the predator-prey relationship but incorporate modern elements of strategy, abstract thinking, and sometimes complex rules. Lambs and Tigers involves the predation of tigers on a series of lambs, while Kaooa is a variant from Africa that includes intricate moves and strategies.

Conclusion: The Enduring Legacy of the Bear Hunt Family of Board Games

From ancient civilizations to modern-day adaptations, the bear hunt family of board games has remained a testament to humanity's fascination with the concept of hunting and survival. These games, while differing in details, all share core themes of strategy, foresight, and tactical skill. Whether it was the ancient hunters of Mesopotamia, the pastoral cultures of Asia, or the ritualistic games of Africa, the influence of these games is undeniable.

The legacy of the bear hunt family lives on in both traditional and digital board games. Its deep roots in human culture, combined with its adaptability, ensure that this family of games will continue to be a source of enjoyment and learning for generations to come.

Alquerque

Alquerque, has a rich history that spans multiple cultures and epochs, influencing the development of other games that we still play today.

Alquerque is believed to have originated in ancient Mesopotamia, making it one of the oldest known board games. Its origins can be traced back to around 2000 BCE, and its history is deeply tied to the early cultures of the Middle East. The game was popular in the ancient Sumerian, Babylonian, and Assyrian civilizations, all of which are known for their advancements in writing, science, and culture. The first evidence of Alquerque can be found in the ruins of Ur (modern-day Iraq), where a 4x4 grid was used for playing a game similar to Alquerque.

Archaeological evidence suggests that the game was not merely a pastime but also a tool for education and training in strategy. Early boards and game pieces were often made from materials like stone, wood, or ivory, and games like Alquerque served as a means to develop skills in logical thinking, problem-solving, and social interaction.

Alquerque’s grid-based nature was designed to replicate strategic warfare, where each player’s pieces represented military forces. The objective was to capture the opponent’s pieces or reach a particular position on the board. The game’s tactical depth could help players think several steps ahead, much like military strategists.

Spread to Ancient Egypt and the Mediterranean

As civilizations expanded across the Middle East, Alquerque spread to other regions, including ancient Egypt. Egypt’s involvement with the game is evidenced by the ancient Egyptian tombs where boards resembling Alquerque grids have been discovered. Egyptian versions were often played by the elite, serving both as leisure activities and as a medium for the expression of status and cultural heritage.

The game also found its way to the Mediterranean through the Phoenicians, who were known for their extensive trade networks. It is believed that the Phoenicians introduced Alquerque to the Greeks and the Romans. The game underwent a series of adaptations as it interacted with different cultures, but its fundamental principles remained the same.

In Rome, the game became particularly popular among soldiers and nobility, where it was known as "Fertulum". The Roman version of Alquerque was similar to its predecessors but had a more refined set of rules. Roman players often used bronze, marble, and ceramic pieces for the game. By this time, Alquerque had evolved into a strategic contest that mirrored the tactical nature of Roman military operations, enhancing its appeal to the aristocracy.

Alquerque’s Evolution into the Islamic World

The Islamic Golden Age, which spanned from the 8th to the 13th centuries, played a pivotal role in preserving and further evolving Alquerque. During this period, the game spread into the Arab world, where it became deeply embedded in the cultural fabric. In Baghdad, Damascus, and Córdoba, scholars and military strategists admired the game's strategic depth, and it became a part of the intellectual tradition of the time.

Alquerque’s popularity in the Islamic world is also tied to the intellectual climate of the period. Mathematics, astronomy, and engineering flourished, and these subjects were often integrated into board games like Alquerque, where logic and planning were essential. Islamic scholars of the time were instrumental in recording the rules of various ancient games, and Alquerque was no exception.

In the medieval Islamic period, Alquerque evolved into more complex forms, with more intricate rules and larger boards. These versions would influence later European games.

Introduction to Europe and the Development of Variants

By the late Middle Ages, Alquerque had made its way to Europe, where it became a favorite pastime in the courts of both France and Spain. It is widely believed that the game was brought back to Europe through the Moorish occupation of the Iberian Peninsula, where it had been a part of the intellectual tradition.